Lista dei cibi da non mangiare

Prestando maggior attenzione via via che si invecchia, bisogna:

ELIMINARE:

- tutti i cibi processati, tranne quelli ottenuti esclusivamente da processi fisici a temperatura e pressione ambiente che non stimolano la secrezione di insulina e a cui non sia stato aggiunto nulla come, ad esempio, l’olio d’oliva extravergine;

- tutti gli oli di semi, tutti quanti (soia, arachidi, ravizzone, colza, canola, girasole, cartamo, zucca, vinacciolo, mais, germe di grano, crusca di riso, cotone, papavero, sesamo, mandorle, noci), ivi compresi gli oli di semi di chia, canapa e lino, ancorché questi ultimi siano ad alto contenuto di acidi grassi polinsaturi omega-3 e a basso contenuto di acidi grassi polinsaturi omega-6; e tutti gli alimenti che li contengono;

- tutti gli zuccheri, i loro sostituti naturali (esempi: miele, preparazioni a base di stevia, incluse le foglie fresche o essiccate, sciroppo d’acero, nettare di agave, sciroppo di yucca, monk fruit o luo han guo, zucchero di noce di cocco, pasta di datteri), gli alcoli di zucchero (esempi: sorbitolo, xilitolo, lattitolo, mannitolo, eritritolo e maltitolo) e, infine, a maggior ragione, i loro sostituti artificiali (esempi: HFCS, saccarina, aspartame, acesulfame K, sucralosio, neotame, advantame); e tutti gli alimenti che li contengono;

- tutti i latti, tutti i lattoderivati interi (incretine[i]) e parzialmente scremati (low-fat), con l’eccezione di tanto in tanto di:

- panna fresca (58% acqua + 35% grasso),

- mascarpone tradizionale (44% acqua + 47% grasso) e

- burro di panna (14% acqua + 83% grasso);

- tutti gli integratori alimentari e le sostanze nutraceutiche perché, anche se contengono virtualmente zero calorie, sono sempre da considerare cibi processati, e, infine,

- tutti i farmaci, solo dopo aver avuto l’approvazione del medico che li ha prescritti, perché, nella maggior parte dei casi, sono tesi al sollievo dal sintomo e non alla rimozione della causa della malattia, e presentano, quasi sempre, una moltitudine di effetti collaterali indesiderati. I medici e le case farmaceutiche dovrebbero essere tenuti al rispetto del primo comandamento medico: “primum non nocere”. Ma la valutazione[ii] rischi – benefici successiva permette di aggirare facilmente questo principio.

RIDURRE prima a una volta la settimana, poi a una volta ogni due settimane, poi a una volta al mese il consumo di:

- tutti i frutti (cariossidi) e i semi delle Poaceae (frumento, farro, spelta, segale, orzo, riso, mais, avena) e i loro derivati (fiocchi e farine), anche se siano stati fatti prima germogliare, essiccare e poi macinare in farine, o fatti fermentare, essiccare e poi macinare, o fatti germogliare, fermentare, essiccare e poi macinare, e tutti gli alimenti che li contengono.

- tutti i frutti (legumi) e i semi delle Fabaceae (fagioli, piselli, ceci, fave, lenticchie), a meno che non siano stati fatti fermentare (tempeh, miso, natto) e tutti gli alimenti che li contengono.

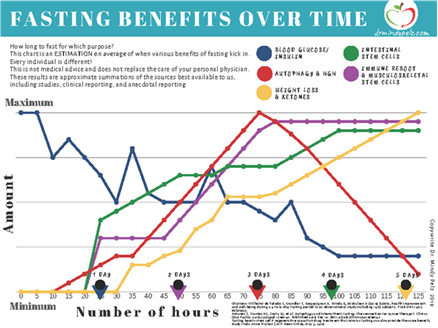

AGGIUNGERE la pratica del digiuno[iii] nelle sue varie forme:

- intermittente (12 – 22 ore),

- medio (2 – 5 gg),

- lungo (oltre i 5 gg).

[i] Incretins are a group of metabolic hormones that stimulate a decrease in blood glucose levels. Incretins are released after eating and augment the secretion of insulin released from pancreatic beta cells of the islets of Langerhans by a blood glucose-dependent mechanism.

Some incretins (GLP-1) also inhibit glucagon release from the alpha cells of the islets of Langerhans. In addition, they slow the rate of absorption of nutrients into the blood stream by reducing gastric emptying and may directly reduce food intake. The two main candidate molecules that fulfill criteria for an incretin are the intestinal peptides glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP, also known as: glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide). Both GLP-1 and GIP are rapidly inactivated by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4). Both GLP-1 and GIP are members of the glucagon peptide superfamily.

[ii] The Lie of Primum non Nocere – Am Fam Physician. 2001 Dec 15;64(12):1942.

In the Latin phrases that get tossed about by physicians, “primum non nocere” (“first, do no harm”) is perhaps the best recognized. “Primum non nocere” is a Hippocratic albatross that today’s physicians have come to understand subconsciously in its appropriate context. Every weapon in the physician’s armamentarium is double-edged; every cure has a potential harm. As physicians we hide this fact in statistical nomenclature in phrases like “percentage of side effects” and other obtuse phrases that try to hide the fact that physicians are not immune to harming. We, as today’s physicians need to allow our patients to understand why and how it is no longer possible to “first, do no harm.”

For every patient I have seen, I have had to rewrite the law. Every drug used, every prescription written, and every procedure has risk; risk of harm, or even death. Today’s physicians interpret “primum non nocere” in a more amicable light: “may the benefits outweigh the risks.” When I reach for a prescription pad, I understand that I might be harming the patient. When I feel that the benefits outweigh the risks for the patient, I continue writing. Often, with God’s help and blessing, I have been helpful to the patients who have come my way. But, I have not always been helpful. I will never forget the pair of kidneys that I harmed with gentamicin. This patient understood something that I did not understand then, and what I am now trying to explain. My patient did not expect that I could cause no harm. He expected me to try to help. When he had acute renal failure from the medication that we used, he understood that bad things happen. We tried something, we failed. After three months, he finally was able to stop dialysis.

Most physicians understand this subtlety and practice accordingly. However, many patients and all malpractice lawyers still cling rigidly to “first, do no harm.” If there is an untoward outcome in a treatment, then wrong was done, and damage will be repaid. In that line of logic, if a physician gives a prescription and harm is done, and the patient is hurt, then the prescription should never have been given. If surgery is performed and the patient dies, then the surgery should never have been done. It is only in not doing that we can give a 100 percent assurance that we will not harm.

I propose that the medical community continue to uphold the same high standard of excellence in caring for patients. I propose that the medical community continue to use therapies only when the potential risks are outweighed by the potential benefits. I further propose that we abandon the outdated lie of “primum non nocere.”

KENNETH LECROY, M.D. (LeCroy Family Medicine – 6630 Colleyville Blvd. Colleyville, TX 76034)